|

Achievements with Antimatterfrom the CERN Courier, November 1983 |

|||

| [ Home ] [ Programme ] [ Neutral Currents ][ W and Z ] [ Press Release ] [ Photos ] [ Courier story ] | ||||

For more information:

Contact the

CERN Press Office

The experiments |

||||||||||||

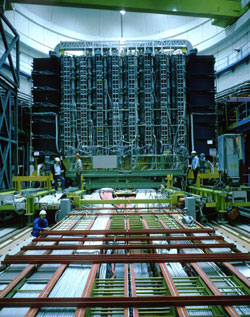

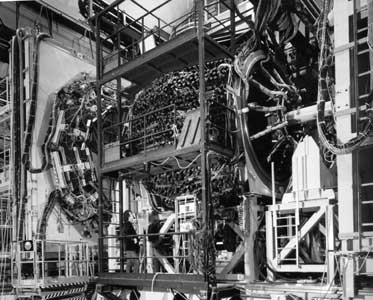

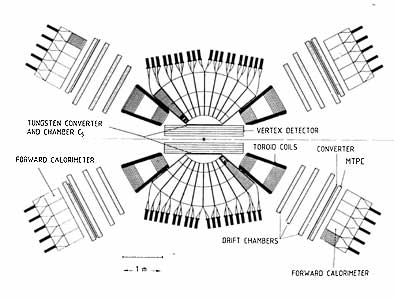

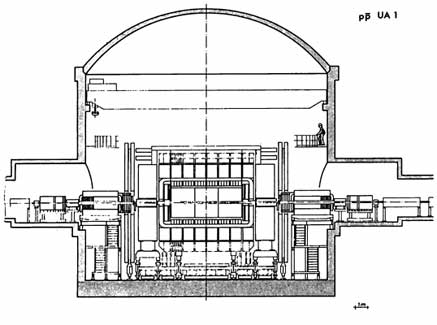

| UA1 and UA2 represent the accumulation of many years of knowledge and experience in the design, construction and operation of particle physics experiments. The CERN Intersecting Storage Rings (ISR), a masterpiece of a machine, was built ahead of its time in the sense that only towards the end of its lifetime was it equipped with detectors that did justice to the available physics. The designers of the UA1 and UA2 detectors had no reason to be caught in the same trap. For the SPS proton-antiproton collider, the aim was to have maximum detector capability right from the start, with adequate tracking and calorimetry (energy deposition measurements); maximum solid angle coverage and powerful data handling systems. Despite their immense size, the two experiments which discovered the W and Z particles are not readily visible to a visitor to the CERN site. The proton-anti proton collisions which the experiments study take place underground in the ring of the SPS machine, and the detectors are housed in deep caverns. The 7-kilometre underground SPS ring was designed and built for 'fixed-target' experiments. For this research, high energy proton beams are made to fly off tangentially from the ring. These beams provide the particles which feed the experiments, installed in large, relatively easily accessible experimental halls. Viewed from the elevated gangways, these CERN experimental halls resemble aircraft hangars, but with beamlines and detectors replacing aircraft. The UAI and UA2 underground halls look very different, but are of the portent of things to come at LEP and other giant new machines to supply colliding particle beams. Detectors studying colliding beams have to surround the region where the beams are brought together. Simply to get the envisaged detectors into the SPS ring would have demanded a mammoth effort of construction and engineering. As if the task of installing a 2000-ton detector with fraction of a millimetre precision in a confined underground space was not enough, there were other restrictions. At the SPS, collider physics would not replace fixed target operation. While the collider experiments were assembled, the machine would continue to operate, and even once the detectors were commissioned, the machine would run alternate periods of fixed target and collider physics according to a prearranged schedule.

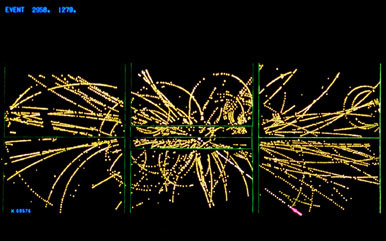

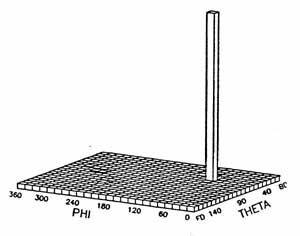

Thus the underground caverns had to be made large enough to provide room for the completed detectors to be positioned in the ring, plus enough ‘garage' space so that they could be assembled without having to shut down the machine. The detectors could be rolled back when a period of data-taking was completed and the SPS reverted to fixed-target operation. In these underground garages and shielded by movable walls, the experimenters could assemble apparatus or tinker with their detector, only several feet away from the intense high energy proton beams in the SPS. The countryside around CERN is far from flat. Although the two experiments are only about one kilometre distant in the SPS ring, the beampipe for UAl's collisions is about 20 metres below the surface, while that for UA2 is some 50 metres underground. The civil engineering for the UA1 premises which began in 1979 used the 'cut and cover' method, while the aptly named 'cathedral' for UA2 was excavated from within. While the earthmoving and excavating teams began work, a vast physics effort was being mobilized across Europe. Responsibility for the various components of the UA1 and UA2 detectors was delegated to the different research centres in the collaborations, including of course CERN. Literally hundreds of man-years of heroic effort went into the design, assembly and testing of the thousands of units for the various subassemblies of the detectors. Wire by wire, and crate by crate, the electronics grew, and piece by piece the equipment for the detectors came together. The high efficiency attained during the 1983 run (80 per cent) bears witness to the thoroughness of this preparation and groundwork. The logistics of this work were farreaching, and sometimes had to overrule physics requirements. The size of some components, for example, was found to be limited by the transport and handling services available. In both detectors, different types of particles are identified and studied by looking at their behaviour as they pass through successive layers of the apparatus, each of which has a specific function. Another problem is posed by the rarity of the phenomena being sought. To be sure of catching a few Z particles over a period of about two months, the detectors would have to be exposed to a few thousand proton-antiproton collisions per second. To examine all this data in detail at once was out of the question, and both experiments use 'triggers' - pre-programmed selection criteria which ensure that potentially valuable physics is recorded on special magnetic tapes for subsequent analysis. Thanks to skilful triggering and subsequent data handling, the captured information can be filtered and analysed even while the experiments are still running. Most interest lies in the triggers which select out those events producing particles flying out at large angles to the direction of the colliding beams, as these particles characterize the violent frontal collisions which shake the constituents of the protons and antiprotons. The UA1 experimentCarlo Rubbia, leader of the UA1 team (see Portrait of UA1, below), describes his immense detector as 'a series of boxes, each one doing what the previous one couldn't do' - a modest description of some 2000 tons of sophisticated precision apparatus packed with advanced technology!The UA1 detector was designed to cope with large numbers of particles, collecting 'unbiased' information from collision products collected over a maximum solid angle. Particle energies are measured both by their curvatures in the internal magnetic field, and by energy deposition (calorimetry). Both electrons and mucins are sought. The 7000 gauss magnetic field is supplied by an 800-ton conventional electromagnet using thin aluminium coils and enclosing a region of 85 cubic metres. Inside the magnet and surrounding the beam pipe carrying the particles are six shells of drift chambers containing 6000 sense wires with image readout, providing a reconstruction of the emerging particle tracks in a cylindrical volume 6 m long and 2.6 m in diameter around the beam crossing point. The reconstructions have an uncanny resemblance to classical bubble chamber tracks. Surrounding this central detector inside the magnet are the 'gondolas' - 48 crescent-shaped modules of lead-scintillator sandwich to catch electromagnetic energy. The outer hadron calorimeter gauges energy flow when particle densities become too great for magnetic analysis. It consists of scintillator slabs and associated instrumentation fitted between the C-shaped iron slabs of the magnet return yoke. Both the electromagnetic and hadronic calorimeters are closed by end-caps. Muons transversing all this are picked up in large slab-like arrays of drift chambers which cover the entire apparatus, giving it a deceptively uninteresting box-like appearance. These muon chambers alone required some 30 kilometres of extruded aluminium! To supplement the detection capabilities of the main detector, additional equipment is installed in the forward/backward regions around the beam pipe on either side of the main detector. A sophisticated microprocessorbased data handling system has been developed which selects out potentially interesting data and copes with the enormous amounts of information produced by each measured collision.

UA2

The annular regions on either side of the central detector are equipped with magnetic analysis and segmented arrays of lead-scintillator shower counters for electromagnetic energy measurement, and drift and proportional tube chambers for electron localization.

The search for W and Z particles was high on the list of priorities in the UA2 design, which concentrates on decays producing electrons. Lead/scintillator sandwich counters identify electrons over a wide solid angle.

Hunting Ws and Zs

Evidence for such jets had been seen in experiments at lower energy, but the higher energies available in the SPS collider made the jets stand out unmistakably from background effects due to other processes. The SPS collider results on jet production were among the physics highlights of 1982. Another initial collider success was the charting of reaction rates (cross-sections) by the UA4 experiment (Amsterdam / CERN / Genoa / Naples / Pisa), installed with UA2, to see how these compared with what was known from lower energies. (UA1 also measures these cross-sections.)

The new experiments in the SPS ring had their first tentative glimpse of 540 GeV proton-antiproton collisions in the summer of 1981. The first task was to make an initial survey of particle behaviour in this newly available energy range. Cosmic ray experiments had previously reported unexplained behaviour, with events containing large numbers of longlived particles but remarkably few neutral pions. Physicists were eager to see if this could be reproduced under laboratory conditions. However neither UA 1 nor the big streamer chambers of the UA5 experiment (Bonn / Brussels / Cambridge / CERN / Stockholm) saw anything radically new. However this setback paid unexpected dividends. Instead of two separate runs, 1982 SPS antiproton operations were merged into one block, which began in October. This was to make for valuable savings in setting-up and running-in.

Even during the run, it had been clear that they were seeing something in the events 'triggered' by energetic electrons. After off-line analysis, the UA1 and UA2 teams found several examples where, amongst the clutter of particles emerging from the collisions, a lone high energy electron had been spat out at a wide angle to the beam direction (high transverse momentum). This isolated electron was found to be roughly back-to-back with 'missing' energy in the calorimeters with no visible associated particle track, hinting at a neutrino. Some thousand million collisions had been seen by the detectors in the 1982 run, but of these, only about one tenth of a per cent were violent enough to provide the right conditions to produce Ws and Zs. Each of these selected collisions produced enough detector information to fill a large telephone directory. Thus it was a dazzling feat of detector know-how and data handling skill by both the experiments to sift through this mass of information so quickly and filter out their interesting events - six at UAl and four at UA2. The results were first presented at the Workshop on Proton-Antiproton Collider Physics, held in Rome in January 1983. The explanation of these events was then still only a whisper. At the meeting, Fermilab Director Leon Lederman had confessed to being impressed by 'the speed at which data was analysed and physics achieved out of detectors of unprecedented sophistication, viewing collisions of novel complexity'.

It took the physicists just a few weeks to convince themselves that they had found the signature of a W particle decaying into an energetic electron and a neutrino, carrying energy but invisible. The formal announcement of the discovery of the W particle by the UAl team was made at CERN on 25 January and later confirmed by UA2. As predicted by the theory, its mass was around 80 GeV. The next step was to track down the companion Z0, the carrier of the neutral current of the weak interaction. However the theory said that these would be ten times rarer than the Ws, and at least several times the amount of data collected in the 1982 run would be required to give the experimenters a good chance of finding some. The SPS operations team were set a goal of 100 inverse nanobarns, roughly four times what was achieved in 1982. Were people being too optimistic in hoping to find the Z0 so soon after the highly successful 1982 run, which had already smashed all records? The 1983 SPS antiproton run began on 12 April, again modestly. But improved techniques and methods began to pay dividends. Magnificent reliability assured a steady supply of the precious antiprotons. Luminosities crept higher and a record figure of 1.6 x 1029 cm-2 s-1 was achieved, more than a hundred times what was seen in the pioneer runs in 1981. The 100 inverse nanobarn target was duly reached on 6 June, one full month before the end of the run! The signature of a Z0 was expected to be much clearer than that of the W. There would be no tricky missing energy to look for. The experiments were looking for clean electron-positron pairs (and, in the case of UA1, oppositely charged muon pairs), carrying more energy than had ever been seen before. The UA1 team triumphantly unearthed a Z0 candidate event on 4 May, from data recorded just a few days before. A first estimate of its mass was around 100 GeV, in the region where it was expected. But this first Z candidate was worrisome as one of its electron tracks looked as though it was accompanied by an energetic photon. But cleaner examples of Z0 decay into electron and positron (and into two muons) arrived from UA1 in the ensuing weeks. On 1 June, the formal announcement of the discovery of the Z0 particle was made at CERN. After the end of the 1983 antiproton run on 3 July, the UA1 and UA2 experiments had between them about a dozen Z0s, centred around 93 GeV, and about a hundred Ws at 81 GeV. As well as W decays producing a lone electron plus neutrino, UA1 has also seen decays producing a muon plus neutrino. But whatever else the UA1 and UA2 experiments may find in the SPS collider, it is clear that a new chapter can be added to the history of science. With LEP and other big machines now being built or planned, we are entering a new era of physics.

Portrait of UA1Aachen Technische Hochschule - muon chambersAnnecy (LAPP) - 'bouchons' (electromagnetic calorimeter end-caps) Birmingham - hadron calorimeter, trigger processor CERN - magnet, compensators, central detector, experimental area, computing, overall coordination Queen Mary College, London - hadron calorimeter, trigger processor Paris, Collège de France - forward detectors Riverside, University of California - 'very very forward' detectors Rome - 'very forward' detectors Rutherford Appleton Laboratory - hadron calorimeter, trigger processor Saclay - 'gondolas' (eletromagnetic calorimeter) Vienna - electromagnetic calorimeter electronics and phototubes This list is not exhaustive, and covers only the initial configuration of the UA1 detector. Helsinki joined later and Harvard and Wisconsin also contributed to development. Next: Results |